Reclaiming The Lost Music of the Second World War

By Gerald Frantzen and Hersh Glagov

“You cannot undo the injustice of the lost lives, of the cruelty. But in the case of the composers, you can do the one thing that would have meant the most to them, which is to perform their music.”-James Conlon

With its Medieval pageantry, damsels in distress, swashbuckling adventures, and a young Errol Flynn in tights, the Adventures of Robin Hood took the country by storm in 1938. To ensure its success, Warner Brothers turned once again to Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Korngold, who had already written the scores for seven Hollywood films, was a perfect fit for this epic tale. With his evocative orchestral colors and brilliant harmonies, the story practically jumped off the screen, earning Korngold his second Oscar. The legend of Korngold and the Hollywood sound was born.

With its Medieval pageantry, damsels in distress, swashbuckling adventures, and a young Errol Flynn in tights, the Adventures of Robin Hood took the country by storm in 1938. To ensure its success, Warner Brothers turned once again to Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Korngold, who had already written the scores for seven Hollywood films, was a perfect fit for this epic tale. With his evocative orchestral colors and brilliant harmonies, the story practically jumped off the screen, earning Korngold his second Oscar. The legend of Korngold and the Hollywood sound was born.

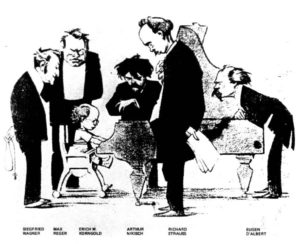

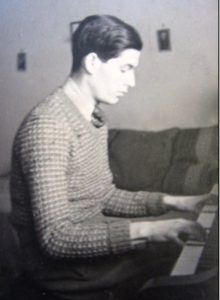

But Korngold wasn’t just a Hollywood composer. Born at the turn of the Twentieth century, he was a child prodigy and a virtuoso pianist whose precocious musical development recalled Mozart. His father was the prominent Viennese music critic Julius Korngold whose blistering reviews struck fear into composers, conductors, and musicians throughout Vienna.

No less a figure than Gustav Mahler recognized Erich’s genius and recommended, to his father’s surprise, that he take composition lessons with Alexander von Zemlinsky. This is ironic as Zemlinsky was often the object of Julius’s most savage reviews.

At the age of 11, Erich became famous almost overnight with his first major composition, a ballet titled Der Schneemann (The Snowman), which Zemlinsky orchestrated. Richard Strauss, upon hearing it, told his father not to send him to a conservatory as he “already knew more than what could be taught to him. “ At the age of 16 Erich premiered two one-act operas: Violanta and Der Ring des Polykrates. Both were challenging, large-scale works that prompted many critics to call him the “future of German music.” Both operas would be performed throughout Europe.

Korngold working on Die Tote Stadt at the Vienna State Opera

In 1919, after serving in the First World War, he finished what many people consider to be his opera masterpiece, Die tote Stadt orThe Dead City. This dramatic opera, with its rich orchestrations, distinctive harmonies, and dark story made Korngold famous worldwide. Giacomo Puccini wrote, upon hearing The Dead Cityfor the first time: “ He has so much talent that he could easily give us half – and still have enough left for himself!” A highly anticipated 1922 production in Munich was shut down by the Nazis, at the time a small political party. This was a full year before the “beer hall putsch” of 1923. Little did anyone know at the time that this was a harbinger of things to come

At the request of the operetta star Hubert Marischka, Korngold turned his energies to adapting and re-orchestrating the Johann Strauss operetta, Eine Nacht in Venedig (A Night in Venice). In 1924, his newfound wealth allowed him to break the parental bonds that held him in check and to marry Lutzi Sonnenthal, an actress. Neither Lutzi nor his orchestrations of operettas pleased his overbearing father. From 1924 to 1933, Korngold would spend most of his time adapting operettas – with one one major exception.

Jan Kiepura and Lotte Lehman Das Wunder der Heliane, 1927

In 1927 he wrote the opera Das Wunder der Heliane. Unfortunately, Heliane premiered at the same time as Ernst Krenek’s Jazz Opera Jonny spielt auf, which was an overnight sensation throughout Europe. Heliane’s lush romantic score seemed dated compared to Krenek’s wild, dissonant jazz opera. It never enjoyed the same success.

In 1929 Erich was invited by the great director Max Reinhardt to create orchestrations for a new production of Die Fledermaus. The show was highly successful and the relationship with Reinhardt would ultimately save Korngold’s life. In 1934 Reinhardt, who had fled to Hollywood with the rise of the Nazi party, asked Korngold to compose the incidental music for his film A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

A scene from Max Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream

For the next few years, Korngold traveled between Hollywood and Vienna, scoring music for over seven different films. At the same time, he had been working on an opera called Die Kathrin, which was scheduled to premiere at the Vienna State Opera in March 1936. The opera, was about a German woman who falls in love with a French soldier and bears his child. The story ran afoul of Nazi censors and the production was shut down. Lutzi, in an attempt to get by the censors, made changes to the original libretto. But by then, it was a moot point. The German music publisher, Schott, which had a long relationship with Korngold, refused to publish Die Kathrin, because of Korngold’s Jewish origins. The London based Josef Weinberger publishing house picked it up instead.

Korngold at Die Kathrin premiere in 1950

In January of 1938 Korngold received a letter from Warner Brothers asking him to score the music for the film The Adventures of Robin Hood. Korngold took this as an omen to move his family to Hollywood. His son Ernst remained behind in Vienna with his grandparents. On March 13, 1938, the Nazis annexed Austria and seized all of Korngold’s property. Fortunately, Korngold’s son and parents, managed to secure a berth on the last train out of Austria. They were only able to retrieve some of his music, and had to leave many manuscripts behind. Michael Haas continues the story:

“While Korngold was away in Hollywood…. Weinberger employees broke into the cellar, recovered what was left of the manuscript (of Die Kathrin), and returned it to Korngold by interleaving sheets between pages of Beethoven, Mozart and other acceptably Aryan composers and posting these to the composer in California.”

Die Kathrin was finally premiered in Stockholm, Sweden in 1939, where it was received harshly by openly anti-Semitic reviewers. Die Kathrin might have seemed old fashioned at the time it was written, but eighty years later that is less important than the intrinsic artistic value of the music. A great tune is a great tune.

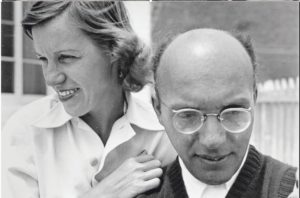

The Korngolds

By 1940, Korngold, safely ensconced in Hollywood with his family, was a composer in exile. He continued to compose for film and helped guarantee the safe passage of his relatives to America, supporting them financially. His success in Hollywood, however was a double edged sword: Korngold’s status as an important classical composer diminished. His friends and fellow exiles chided him that composing film scores was beneath his talent. By time the war had ended, he left the studios and tried to pick up where he had left off as a “quote un-quote” serious composer. He wrote a symphony, which he was unable to get anyone to perform. In 1951 Die Kathrin received its long-awaited Viennese premiere. The production, despite good reviews, was shut down after a short run after the lead soprano received death threats.

Although the Nazis had been defeated, anti-Semitism lingered on in Viennese culture. By this time, Korngold had become a musical anachronism. He music was too romantic and a reminder of a pre-war Europe that was no longer valued. No halls in the U.S. or Europe would play his music. He died of a heart attack on November 29, 1957. The Vienna State Opera flew the black flag of mourning as a sign of respect, but, according to Korngold biographer Brendan Carroll, when Korngold’s son told Lutzi about it, she replied: “It’s a little late.”

Korngold was one of many composers who were forced into exile during the Second World War. The ascendency of the Nazi party and their systemic effort to eliminate Jews from all cultural life would take a serious toll on composers, artists, and musicians alike. The Nazis co-opted the word entartet (degenerate) as a label for all art by Jews as well as any art or music that did not fit the aesthetic or ideological sensibilities of the Nazi Party. In 1933, they created the Reichsmusikkammer, or State Music Bureau, which was introduced to ensure that Jewish composers’ works, along with modernist music, Jazz, and swing, were banned. Jewish artists could not possess licenses for performing in public and were no longer allowed in concert halls. In the case of music composed by non-Jews to texts by Jewish librettists, the inconvenient names were simply expunged from the concert program.

Richard Strauss, in one of the more unfortunate choices he made in his life, accepted an appointment as the first head of the Reichsmusikkammer. He was later dismissed after saying, in a letter to his Jewish librettist, Stefan Zweig, that he was merely “play-acting.” Nonetheless, his tenure there was effectively an endorsement of Nazi policy. Although his behavior during the Nazi era was ambiguous, Strauss did not repudiate or work against the regime. Ultimately, his actions appear to have been motivated by vanity and self-preservation.

Alexander Von Zemlinsky

For the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, the war years would prove to be especially difficult. The Nazi era brought exile, but beyond that, the destruction of the artistic atmosphere in which he had come of age and flourished. A Jew by birth, he converted to Protestantism in 1895. By the turn of the century, he had established himself not only as a respected late Romantic composer, but also as one of the leading composition teachers in Vienna.

His students are a ‘who’s who” of the important composers of the time. Karl Weigl, Alban Berg, Anton von Webern, Hans Krasa, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Arnold Schoenberg all studied with him. Zemlinksy was the only teacher Schoenberg ever had. His early operas, Saremma and Es war einmal,were largely influenced by Brahms, with the latter being premiered by the Vienna State Opera under the baton of Gustav Mahler.

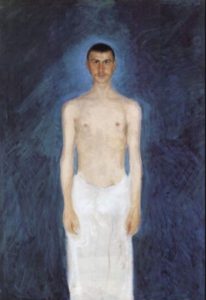

Theodore Gerstl Self-Portrait

Zemlinksy and his circle of acquaintances were fraught with scandal and intrigue, all of which had an impact on his compositional life. His sister Mathilde, who was married to Arnold Schoenberg, had an affair with the artist Richard Gerstl. Schoenberg caught the two “in flagrante delicto” at his country villa. Eventually, Schoenberg persuaded Mathilde to remain with him and forbade her from seeing Gerstl. This was too much to bear for the young painter and he hung himself. Zemlinsky drew upon the affair in his opera, Eine Florentinische Tragödie. The opera centers on a love triangle between a cuckolded husband, his wife, and her lover.

Zemlinksy himself had been in a torturous relationship with none other than Alma Schindler (later Alma Mahler). He had been hired by Alma’s father to teach her composition. Alma, considered to be “the beauty of Vienna,” was at first repulsed by him. In her diary she referred to him as a “chinless, toothless, unwashed gnome.” Despite her gratuitous use of adjectives he eventually won her over. We will assume that it was his winning personality. Their love affair lasted for two years, but due to pressure from her family, she abruptly broke off the romance and left him for Gustav Mahler. Zemlinksy was devatsted.

The broken relationship inspired two works, Die Seejungfrau (The Little Mermaid) a fantasy for orchestra, and the opera, Der Zwerg (The Dwarf). There’s no doubt that Zemlinksy was referencing his failed relationship with Alma, when he set this story of a dwarf’s unrequited love for a princess. The show premiered in Cologne in 1922 to great acclaim.

By the late 20s Zemlinksy held important teaching positions first in Prague and then in Berlin.. In 1932 he was he was dismissed due to a new Nazi law that forbade Jews from working in State service positions. He moved back to Vienna. After the Austrian Anschluss, he fled to Prague and then to New York, where he was in talks with the Met to premiere a new opera called Der König Kandules. It was rejected by the Met for having a poor libretto.

Unlike Schoenberg, who found a job in California, Zemlinsky found himself destitute and unknown in New York. After a series of strokes he stopped composing altogether. He hated all the noise of the city and moved to Larchmont, New York where he died of pneumonia in 1942. His music, and especially his operas, deserve a place in the repertoire.

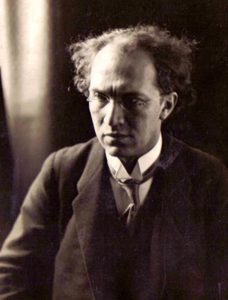

Franz Schreker

In the case of the Viennese opera composer Franz Schreker, the restrictions of Nazi era brought a brilliant career to a sudden end. Schreker was one of the most popular composers of the Weimar era. Born to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, he compromised by practicing neither religion. Schreker wrote impressionistic music that focused on tonal colors, much like Claude Debussy and Richard Strauss. Everyday noises became part of his aptly called cinematic soundscape.

This is most evident in his first opera, Der Ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), which had its premiere in Frankfurt in 1912. The show, with its mixture of fantasy and realism, was an instant success and brought him overnight fame. Zemlinsky conducted the Czech premiere in Prague. Richard Tauber and the composer’s wife, Maria Schreker , performed in a highly-acclaimed Berlin production in 1925.

The story follows Fritz, a young composer, and Grete, a village girl. Fritz is in love with Grete and promises her that he will marry her as soon as he writes a great piece of music and discovers the mysterious distant sound he hears.

Maria Schreker as Els in Der Schatzgräber

Schreker was a complex man. His wife Maria, whom he met in 1908, was 17 years younger than he was. Not long after they were married, he had an affair with Alma Mahler (Gustav Mahler had just died) before she ran off with the painter Oskar Kokoschka. Schreker dedicated his next opera, Das Spielwerk und die Prinzessin, to Alma. The show was a failure. His wife, Maria, renowned for her beauty and her voice was rumored to be having affairs with women during this time. She sang in the premiere productions of many of her husband’s works , including his 1916 opera Die Gezeichneten and the 1919 opera Der Schatzgräber. The popularity of the these last two shows, combined with Der Ferne Klang, meant that Schreker rivaled Richard Strauss in the number of his works being performed on European stages. Many critics at the time thought that if Die Gezeichneten had not come out during the First World War, it would have found its way into the standard repertoire.

In 1922 he wrote the opera Irrelohe (Flames of Madness), which was overtly sexual in nature. But, by now, Schreker’s music seemed out of step with the times. “Zeit Oper,” or operas that had contemporary settings and satirical plots were all the rage. The trend was led by Krenek’s jazz opera Jonny Spielt auf and Max Brand’s Maschinist Hopkins (inspired by the film Metropolis).

Maria Schreker

Schreker taught at the Berlin Music Hochschule for 20 years, until 1932, when a professor of violin accused Schreker of appointing too many Jews to the faculty. Schreker was forced to resign. At the same time, his latest opera, Der Schmied von Ghent, was both praised and booed at its premiere. Out of work, and in an increasingly hostile environment, he desperately tried to find a position in the United States. The stress, however, was too much for him and he suffered a stroke and died in March of 1934. He was an early victim of the new regime. His musical legacy was already jeopardized by his professional colleagues who were envious of earlier successes.The Nazis would ensure that his legacy was destroyed.

For Hans Gal, the esteemed founder of the Edinburgh Festival, the sense of safety provided by England in the Second World War was a double edged sword.

Hans Gal

After serving in the Austrian Army during the First World War, he completed his first opera, Der Arzt der Sobeide (Sobeide’s Doctor). He wrote it while stationed in the Carpathian mountains during the war. This comic opera brought him recognition and helped him to build his career. In the early 1920’s, Gal enjoyed much success in his academic, creative and personal life. In 1923 he wrote what many consider to be his best opera, Die heilige Ente, orThe Sacred Duck. The opera based on a Chinese fairytale about a duck breeder named Yang who delivers a duck to the Mandarin’s palace, and falls in love with the Mandarin’s wife, Li. The duck is stolen and the Mandarin orders that Yang be executed. The gods decide to have some fun and switch the brains of Yang and the Mandarin. Yang (now in the body of Mandarin) commutes the sentence for the Mandarin (now in the body of Yang). But he also criticizes the gods (85), who angrily reverse the change. The duck suddenly reappears, and the Mandarin, considering this a miracle, offers to make Yang a nobleman. Yang, content to remain who he is, leaves to seek his fortune elsewhere.

Die Heilige Ente, The Sacred Duck, 1932

Die Heilige Ente was an immediate success and was

performed in opera houses throughout Germany. The opera, with its unique “oriental orchestral colorings,” owed some of its success to the contemporary fascination with all things Chinese. Puccini’s Turandot, part of the same trend, opened a year later. Gal’s opera would remain popular in German opera houses until 1933.

In the late 1920’s Gal was one of two editors of the complete works of Johannes Brahms, a seminal edition that is still in use today. Upon the recommendation of conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler, he was made the head of the Mainz Academy in 1929. He remained there until the Nazis took over in 1933. The local press called for his resignation, stating unequivocally : “ Away with the Jew Gal. Mainz Conservatory for German art!” A swastika was hung above the conservatory and Gal was forced out. He returned to Austria.

Ironically, Gal, according to the Hans Gal Society, attended the same concert that Hitler attended on the 50thanniversary of the death of Richard Wagner. Gal, after observing Hitler, opined that “no one could possibly take him seriously.” His opera Die Beiden Klaas, which was to have its premiere in 1933, was cancelled. By 1938 with the Austrian Anschluss, the Gals would make their way to Great Britain. His mother Ilka and sister Edith would remain behind with their Aunt Jenny in Weimar, Germany. The mother died in an accident in 1942. Edith and Jenny, who were soon to be transported to a concentration camp, committed suicide instead.

Han Gal internment on the Isle of Wight

The Gals struggled to make ends meet in England. After Churchill’s famous exhortation of 1940 to “collar the lot” (referring to enemy aliens), Gal, despite his Jewish heritage, was sent to an internment camp on the Isle of Man. He was there for almost four months. As these internment camps housed many highly-educated refugees, they quickly became centers of cultural education. There were lectures, chamber music concerts, art classes, and so on. Whereas the Nazis presented the Theresienstadt internment camp as an artists’ colony whose Jewish residents were supposedly thriving, ironically it was the Jewish refugees interned in Britain who were able to create the real thing. Nonetheless, it was still internment, and, of course, the British notion that Jewish refugees could possibly be a “fifth column” that supported the Nazis was ridiculous.

Gal was released in August 1940. By the end of the war, he had found a position as Professor of Music at the University of Edinburgh. His youngest son, Peter, did not adjust well to life in Edinburgh, and committed suicide. The Gals would have one more child, Eva. In 1947, along with fellow exile Rudolf Bing, he established the Edinburgh Festival. Gal would remain (106) active in Edinburgh until his death in 1987 at the age of 97. His music has largely been forgotten, until recently. In 1990, his opera “Die Beiden Klaas” finally had its long-awaited premiere. Neither Gal nor his wife lived to see the work performed.

Like Zemlinsky, Egon Wellesz embodied the Viennese Fin de Siecle art and music scene. A lecturer in musicology at the University of Vienna, he was the first Austrian conductor to bring the works of Claude Debussy to Vienna, and Debussy’s influence can be heard in Wellesz’s early works. As a composer, he is often referred to as the “forgotten modernist.” He was one of the four original members of the Second Viennese School founded by Arnold Schoenberg, which also included Anton Webern and Alban Berg.

In 1920 he published a biography of Schoenberg – a full year before Schoenberg developed his 12-tone system! He had met Schoenberg while teaching at the Schwarzwald School. The school was really more of a salon set in the Austrian countryside. Here, Wellesz rubbed shoulders with the painter Oskar Kokoschka, the architect Adolf Loos, and the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal. He also met his future wife, Emmy, at the school.

Egon Wellesz

Wellesz would become the only composer, other than Richard Strauss, for whom Hofmannsthal would provide a treatment for an opera and a ballet. From his meeting with Hofmannsthal, Wellesz would write, between 1924 and 1926, the “Heroic Trilogy.” The shows were a fusion of opera and dance, antiquity and modernism. They were a critical success, but audiences did not know what to make of them. Wellesz’s trilogy was a forerunner of developments in modern dance.

During the Weimar Period, Germany was providing public funding for operas. In fact, in 1928 there were over 60 new opera premieres. Obviously it was a good time to write an opera, and Wellesz started work on Die Bakchantinnen. The opera was premiered in 1931 at the Vienna State Opera. Wellesz, who wrote the libretto, based the opera on the play The Bacchae by Euripides. It is the story of Zeus’s jealous wife Hera tricking his lover Semele into asking him to show himself in all of his Godlike glory. Zeus obliges, but, in so doing, he incinerates Semele. Wellesz changed the jealous wife Hera to her sister Agave. The show was the culmination of Wellesz’s fusion of dance, spoken chant, and syncopated rhythms. In keeping with the Greek theatrical tradition, it uses a chorus as a means of commenting on the dramatic action, and, according to Michael Haas, “moving rhythmically in such a way as to provide additional narrative illustration.”

Die Bakchantinnen, before it could be more widely heard, was shut down by the Nazis. In 1938, Bruno Walter invited Wellesz, along with Ernst Krenek, to Amsterdam to hear Wellesz’s “Prospero” and Krenek’s Second Piano concerto performed. This proved to be fortuitous. The Anschluss happened that weekend, and Wellesz, Walter and Krenek all fled to England to seek refuge.

Wellesz, a devout Catholic, despite his Jewish heritage, benefited from the British who, to quote Michael Haas, “accorded political opponents to Nazism a higher status than Jews, who were deemed to be fleeing Germany out of less significant ‘racial’ grounds.” Wellesz would always say that he and his wife were forced to leave Austria because they were “monarchists.” Wellesz, like Hans Gál, was sent to an internment camp on the Isle of Man in 1940. Initially, he found the camp to be almost like a spa with a thriving artists’ community, albeit with only male residents. In the long run, however, internment would take its toll and Wellesz would suffer a total mental breakdown. Ralph Vaughan Williams, the distinguished English composer, interceded to get Wellesz released from the camp.

Viktor Ullman

Wellesz did not compose anything from 1938 until 1943. He contributed to the famous Groves Dictionary of Music before joining the faculty at Oxford. He composed his first symphony there in 1945, at the age of 60. He would eventually compose nine symphonies, although his works have largely been forgotten. While the composers we have been talking about had varying degrees of success in exile, there were other composers who never got the chance. Viktor Ullmann studied with Schoenberg and Zemlinsky. He worked as a conductor at the New German Theater in Prague. In 1929, while working in Switzerland, he became deeply interested in the work of philosopher Rudolf Steiner. He even quit music for a while to operate an anthroposophical bookstore in Stuttgart. When this endeavor failed, he returned to music. Several of his works reflect his interest in anthroposophy. When the Nazis took control of Czechoslovakia in 1938, Ullmann tried unsuccessfully to emigrate. He did, however, manage to send his children to safety in England, thanks to the Kindertransport initiative. In September 1942, Ullmann and his wife were taken to Terezin.

Ullmann was very productive in the two years he spent in the camp, serving as pianist, conductor, lecturer, and critic. He also composed several new pieces, including his opera, Der Kaiser von Atlantis. Petr Kien, a Czech poet and painter who was also interned at Terezin, supplied the libretto. The Emperor of the title tries to enlist the help of Death in exterminating unwanted elements from his realm. Insulted, Death, who objects to “the mechanization of modern life and dying,” not only refuses, but retaliates by making it impossible for anyone do die.

In 1944, as it became evident that the Germans were going to lose the war, they stepped up the pace of transports to the extermination camps. In September and October of that year, the remaining inmates of Terezin were taken away. Ullmann died at Auschwitz in October of 1944. Ullmann wrote surprisingly, that his compositional style crystallized during his time at Terezin. Stripped of everyday comforts, he felt that every note took on a terrible urgency:

“In Terezin, where in daily life one has to overcome matter through form, where everything musical stands in direct contrast to the surroundings: here is a true school for masters.”

Ullmann’s renewed dedication to his craft in the face of unimaginable horror is remarkable.

Many of these composers have been the subject of renewed interest in recent years. Hans Krasa, another student of Zemlinsky, was deported to Terezin in 1941. It was there that he reconstructed his children’s opera, Brundibar, which he had written for a competition before the war. It became a favorite of the children of Terezin and was performed over 55 times. It was featured in the Nazi propaganda film, “The Führer builds a city for the Jews,” As the words were sung in Czech, the German SS guards didn’t understand the story, which was an allegory of the Nazi dictatorship. Krasa would die in October 1944, two days after being transported to Auschwitz.

Gideon Klein

Another Czech Jewish composer, Gideon Klein would suffer a similar fate. Klein, who was born in 1919, was a naturally gifted pianist and by 1939 was studying composition with the noted Czech composer Alois Haba. It was a difficult time to be a student, and eventually his studies were cut short as the Nazis closed the Universities. An attempt to study abroad in London was aborted and Klein went into hiding, performing under a pseudonym and even hosting a salon for musicians and writers.

He was eventually transported to Terezin in 1941. He was involved in teaching music to the orphans there. He also performed concerts on the piano, accompanied opera performances and composed a series of works of his own. Klein was eventually sent off to Auschwitz where he perished in 1945. His music survives for two reasons: he entrusted a suitcase full of his early manuscripts to a friend who left the suitcase unopened until 1990. The other reason was the tireless efforts of his sister Eliska who championed his music after the war. One of the pieces that he wrote at Terezin was the string trio. A friend of Klein’s preserved the manuscript and gave it to Eliska after the war. Let’s listen to Klein haunting piece.

Many exiled composers struggled with the difficulty of assimilating into a new country. Both Gal and Wellesz, though they spent almost half of their lives in Britain, always felt the reluctance of the British to fully embrace their music. For Kurt Weill, the adjustment to his new country was a little smoother.

Lotte Lenya and Kurt Weill

Kurt Weill , born at the turn of the century in Dessau, was the son of a cantor. He had his first major success with the one act opera Der Protagonist. In 1927 he started his collaboration with Bertholt Brecht, creating several anti-establishment shows. Brecht”s provocative political theater and Weill’s discordant, Jazz-infused style were a perfect match. In 1928 they wrote The Threepenny Opera, which wasn’t really an opera, but a rather a play with music. This thinly-veiled satire of capitalism included some of Weill’s most memorable tunes and was an enormous success. In 1931, they premiered the opera The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, a mordant critique of contemporary society and it hypocrisies and injustices.

Mahagonny took modern opera in a new direction. Set somewhere in America in the fictitious town of Mahagonny , the story revolves around a group of outlaws who are focused on material pleasures. The main protagonist, Jimmy Mahoney, gets into trouble for having “committed the one unforgiveable capital” sin of having no money. He is tried and executed, and the town, having a survived a hurricane and various other calamities, falls apart “in the chaotic aftermath of the trial.” Let’s listen to this song from the show in which the prostitute Jenny refuses to help the desperate Jimmy out of his troubles, since they were his fault in the first place.

Of course, the Nazis found Mahagonny intolerable. By 1933, after numerous productions sparked riots and were shut down by the Nazis, Weill fled to Paris and eventually to New York. In 1936 her teamed up with the playwright Paul Green, to write the anti-war show Johnny Johnson, a show we premiered in 2017.

Unlike Zemlinksy, Weill was able to work successfully in a whole new idiom, in fact pioneering a new sound for the American musical. He worked throughout the remainder of the war, creating such shows as Lady in the Dark, Street Scene, Lost in the Stars, and One touch of Venus. Weill died of a heart attack in 1950. The composer and critic Virgil Thomson remembered Weill as “the most original single workman in the whole musical theater, internationally considered, during the last quarter century… Every work was a new model, a new shape, a new solution to dramatic problems.”

Jaromir Weinberger

The Czech composer Jaromir Weinberger, like Korngold, was a child prodigy. By the age of 10, he was composing. He studied composition, first in Prague, and later with Max Reger in Leipzig. Reger was a master of counterpoint, and his rigorous approach can be heard in Weinberger’s music. In 1922, he took a position at Cornell University in the United States. While there, he discovered an affinity for American writers. Other than that, his stay in America was not a happy one, and he returned to Czechoslovakia, where he was appointed director of the National Theater in Bratislava. While his output is considerable, he was known for just one of his compositions: the opera, Der Dudelsackpfeiffer (Schwanda the Bagpiper, 1926).

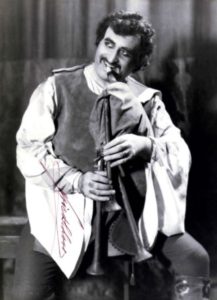

Friedrich Schorr as Schwanda in Schwander der Dudelsackspfeiffer

Schwanda the Bagpiper was the most popular opera to emerge between the world wars. It was given thousands of performances at hundreds of opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera in New York. The opera draws on Czech folk music, much as Smetana and Dvorak had done earlier. The story is a mix of folk tale and fantasy. Schwanda’s bagpipe playing melts the icy heart of a queen and later saves him from execution, but he’s still not safe until the crafty Babinsky, a Robinhood-like figure who also has designs on Schwanda’s wife, beats the Devil at cards and rescues Schwanda from the fires of Hell. The libretto was by Max Brod, who was a good friend of Franz Kafka. Make of that what you will.

With the Austrian Anschluss in 1938, Weinberger was forced to flee. His flight of exile took him through France, England, and Canada before he arrived once again in the United States. He continued to compose. In another parallel with Dvorak, Weinberger was inspired to write music based on American folk music and subject matter. For example in the 1940s he wrote a Lincoln Symphony and an orchestral tone poem The Legend of Sleepy Hollow . But his losses, both as a composer and as a human being, were insurmountable. His mother and sister were killed in the camps. In America, Weinberger struggled with financial worries and with depression. The cultural world in which he had once thrived no longer existed. Weinberger, like the other exiled composers, had to try to live and work in a world he no longer recognized, a world that now found his music quaint and old-fashioned. Unlike Weill or Korngold, his efforts to adapt were not successful. Wracked by illness and depression, he took his own life in 1967. If Schreker was the first composer to fall victim to the Nazis, Weinberger, over 20 years after the end of the war, was perhaps one of the last.

When we present a concert like this one, the question arises: How good is this music? Does it deserve to be heard on its own merits, or does it get a sort of “boost” from the fact that the composers were the victims of persecution? The answer is, we don’t know! In the history of the composers whose works we heard today, the test of time was artificially interrupted, as a systematic effort was made to wipe out the works of Jewish artists or any artists that didn’t fit within the narrow racial, ideological, and aesthetic boundaries of the Nazis.

James Conlon, conductor of the LA Opera, and a leader in the field of recovering these lost works, puts it this way:

“I don’t believe that every piece has to be a masterpiece. It’s not about that. It’s about feeling the spirit of the time, the Zeitgeist. [It’s wrong to think that] if you don’t know about it, it’s not good. History has been written with an enormous hole in it . . . You have to revisit the subject. We should not sit back on the assumption that all the votes are in.”

OUR PROGRAM

Pierrot’s Tanzliedfrom Die tote Stadt Erich Wolfgang Korngold

William Roberts, baritone

Ich soll ihn niemals, niemals mehr sehn from Die Kathrin Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Jenny Schuler, soprano

Mädchen, nimm die blutende Orange from Der Zwerg Alexander von Zemlinksy

Gerald Frantzen, tenor

Ein hohes, hehres Ziel schwebt from Der Ferne Klang Franz Schreker

Gerald Frantzen, tenor

Alison Kelly, soprano

Mandarin Aria from Die heilige Ente Hans Gál

William Roberts, baritone

Das war ein Einziges werden from Die heilige Ente Hans Gál

Gerald Frantzen, tenor

Alison Kelly, soprano

Agave’s Aria from Die Bakchantinnen Egon Wellesz

Jenny Schuler, soprano

Arie des Todes from Der Kaiser von Atlantis Viktor Ullmann

William Roberts, baritone

String Trio, Lento Gideon Klein

Agnieszka Likos, violin, Hersh Glagov, viola, Patrycja Likos, cello

Wie man sich bettet so liegt man Kurt Weill

from Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny

Alison Kelly, soprano

Babinsky’s Ballade from Schwanda der Dudelsackpfeiffer Jaromir Weinberger

Gerald Frantzen, tenor

Marietta’s Lied from Die tote Stadt Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Jenny Schuler, soprano