On July 24, 1931, a highly anticipated new operetta made its debut at the annual operetta festival in Leipzig, Germany. It premiered during a challenging time. Unemployment in Germany was at a record high, and just eleven days before, the country’s second-largest bank had gone bankrupt, triggering panic and riots in cities across the nation. In response, the Weimar government, itself teetering on the brink of collapse, had closed all the banks for two days and the stock markets for two months.

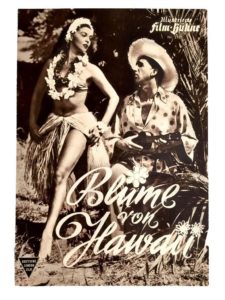

The operetta’s composer, a Hungarian named Paul Abraham, was well aware that people wanted escape into another world, ideally one populated by fantastical characters and exotic locales. A year earlier he had achieved box-office success with the operetta Viktoria and Her Hussar, which was set partly in Japan and had a score influenced by East Asian music. Now, with his team of collaborators, Alfred Grūnwald, Fritz Lōhner Beda and Emmerich Fōldes, Abraham had written an operetta set in a storied island group in the North Pacific: Blume von Hawaii, or The Flower of Hawaii. With its lush orchestration and catchy song-and-dance numbers, Blume von Hawaii was a smash. It soon moved on to Berlin and then across Europe. To capitalize on the operetta’s success, even a film version was released to theaters in early 1933. But then came World War II and, after it was over, huge changes in the world of entertainment. Except for a brief revival of its music in the early 1950s, Blume von Hawaii was largely forgotten.

Paul and the pua: In the 1930s, one of Germany’s most celebrated composers Paul Abraham wrote an operetta set in Hawai‘i: Blume von Hawaii. The musical was a huge hit, toured Europe, was adapted into a film and then all but disappeared.

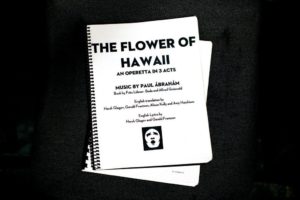

Seven years ago Gerald Frantzen—founder and artistic director of the Chicago-based theater company Folks Operetta—decided with his wife, Alison Kelly, to pursue a revival of Blume von Hawaii. During its heyday the show had been performed on hundreds of stages but never in English. So Frantzen and Kelly, who along with collaborator Hersh Glagov are fluent in German, translated the operetta’s original libretto from German into English. And while they wanted a show that stayed true to Abraham’s original, they were also determined to be sensitive to Polynesian sensibilities and to portray the Islands in an accurate and respectful way; for help with this part of the revival, they collaborated with David Acevedo, artistic director of Chicago’s Hōkūle‘a Academy of Polynesian Arts, and with June Tanoue of Hula Chicago: Hālau i ka Pono.

On June 29 of this year, nearly eighty-eight years after its debut in Leipzig, The Flower of Hawaii was reborn on a Chicago stage. Much that had made Abraham’s show such a hit remained, but there were additions: The show in Leipzig definitely did not open, as it did in Chicago, with an actor in a malo (traditional Hawaiian loin-cloth), blowing a conch shell to mark the four cardinal directions.

The story that The Flower of Hawaii tells draws on Hawaiian history and culture—loosely. Abraham’s work nods to the real lives of Hawaiian monarchs and subjects: the 1893 overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani and the annexation of Hawai‘i by the United States in 1898. But Abraham set his story in the late 1920s and early 1930s, wanting to incorporate jazz, ragtime and more contemporary Hawaiian music as well as dances such as the fox trot and the Charleston.

The operetta revolves around the fictionalized love story of its two lead characters: Princess Laia, a former crown princess of Hawai‘i, and Prince Lilo-Taro, her childhood sweetheart. Laia’s character was inspired by Princess Victoria Ka‘iulani; Prince Lilo-Taro by Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole. At the beginning of the operetta, Laia is clandestinely returning home to the Islands from exile; the territory’s American governor, hoping to strengthen his control of the archipelago, had tried to prevent Laia from coming back. She arrives in disguise, as a famous French singer named Suzanne Provence. In on the ruse and accompanying Laia to help her is Provence’s accompanist and purported boyfriend, the musical star Jimmy Fox. To avoid the governor’s scrutiny, Laia and Fox sail to the Islands as guests aboard a US Navy ship—and its captain promptly falls in love with the enchanting woman he believes is Suzanne Provence. After Laia arrives in Hawai‘i, Lilo-Taro also returns home; unlike the princess, he arrives with much fanfare. Quickly, the governor hatches a scheme to have Lilo-Taro marry his niece, and to say that complications ensue would be an understatement.

With its lush orchestration and numerous song-and-dance numbers, The Flower of Hawaii is pure escapism. But politics is never far away, and throughout the operetta it is clear that the Hawaiians portrayed onstage resist annexation. The character of Kanako-Hilo, leader of the Royalist Party, remains a steadfast and proud Hawaiian nationalist; he eventually reveals the identity of Princess Laia and quickly works to have her crowned as queen of Hawai‘i. Inspiration for Kanako-Hilo came from the life of Robert William Kalanihiapo Wilcox, a leader of a 1895 counterrevolution to restore the Hawaiian monarchy.

How did Abraham and his collaborators get the idea for an operetta that examined the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom and the Islands’ subsequent annexation to the United States? A clue may be found in Abraham’s score, which makes frequent use of Hawaiian steel guitar. By the time Abraham wrote Blume von Hawaii, Hawaiian music had become a worldwide phenomenon, and while it’s not certain whether Abraham or his collaborators met any Native Hawaiian musicians, it’s possible, even probable. After the end of World War I, Native Hawaiian musicians such as Joseph Kekuku (who is recognized today as the inventor of the steel guitar), Mekia Kealakai and William Kamoku toured Europe extensively and thrilled audiences with their virtuosity. Many songs in their repertoire were sung in Hawaiian and celebrated the Hawaiian monarchy.

Another possible influence can be found in the Hawaiian love of opera, which dates in the Islands to at least 1854. Hawaiian royalty were frequently involved in opera performances: In 1861 Queen Emma appeared in the chorus of an operatic stage production, and her husband, King Kamehameha IV, was the stage manager. Twenty years later Princess Miriam Likelike and Princess Bernice Pauahi appeared together in the chorus during a production of the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta HMS Pinafore. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, two Native Hawaiian opera performers achieved critical success in Europe: Ululani McQuaid Robertson, a coloratura soprano from O‘ahu, became well known for her performances in Paris in the title role of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly. And in June 1929, Tandy MacKenzie made his opera debut in Cannes as Rodolfo, the lead male role in Puccini’s La Bohème. In addition to his operatic roles, MacKenzie also toured Europe as a successful solo performer, and he always sang a repertoire of Hawaiian songs, many of which celebrated the Hawaiian monarchy. Even if Abraham or his collaborators hadn’t attended one of MacKenzie’s performances, they would certainly have been aware of him; MacKenzie had signed a contract with the Bavarian State Opera.

Abraham’s own life shared some parallels with those of his Native Hawaiian characters. Born in Hungary in 1892, he too was the subject of a monarchy that no longer existed, the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Like the musicians who had left Hawai‘i, Abraham had left his native Hungary for greater financial opportunities in Austria and Germany. To survive, the Hawaiians and Abraham had had to learn to be successful in two worlds.

The operetta revolves around the fictionalized love story of Princess Laia and Prince Lilo-Taro her childhood sweetheart. In the Chicago production, Princess Laia is played by Marisa Buchheit, seen in the center in disguise as French chanteuse Suzanne Provence.

In Germany, Abraham became known as the king of the operettas. But less than a month after the December 1932 premiere of his last hit operetta, Ball im Savoy, Abraham’s world changed dramatically. On January 30, 1933, Hitler was named the chancellor of Germany, and within a short time Jewish composers such as Abraham, even those without a political message, were banned. Abraham left Berlin, settled in Vienna and resumed writing. But anticipating Germany’s takeover of Austria, he fled back to his homeland of Hungary. When the mood there changed, he made his way to the United States. There his mental health deteriorated and he was eventually institutionalized.

In 1953, while Abraham was still hospitalized, the songs from Blume von Hawaii were used in a new German film. While the story bore no resemblance to that of the original operetta, the movie remains noteworthy because of its musical performances by a celebrated family of Polynesian musicians, the Tau Moes. And after a German magazine published a story in 1956 revealing that Abraham was in an asylum in New York, a group of prominent German supporters worked to secure his return. It was complicated—Abraham had never been a citizen of Germany and was still a citizen of Hungary, which was then under the control of the Soviet Union—but in the end he was able to return to Germany. His last years were peaceful, and he died less than nine months after Hawai‘i became a state.

The director of the Chicago production, Amy Hutchison, worked with Chicago’s Polynesian community to reformulate any dated and inaccurate portrayals in Abraham’s original script. Hutchison also incorporated Hawaiian language, dance and customs into the new show.

“Operas are 100 percent singing. Operettas are 75 percent singing and 25 percent speaking. Musicals are 50 percent singing and 50 percent speaking,” explains Frantzen, noting that Oscar Hammerstein, Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern and Irving Berlin all worked on operettas in the early part of the twentieth century. But after World War II the era of the German-language operettas of Vienna and Berlin was essentially over. “Anything that transported people back to prewar Europe was frowned upon,” says Frantzen. “Despite the fact that this was music by a Jewish composer who had been drummed out of Germany, the rest of Europe did not want to be reminded of anything that sentimentalized Germany or Vienna.”

But Frantzen and Kelly believed it was time to resurrect the lost German-language operettas and started Folks Operetta in 2006 with a mission to do just that. “We had been performing together on the road for over ten years,” says Frantzen. “We had spent a significant time in Germany. It was there we came across shows and operettas we had never heard of before. The music was too good not to be performed.

“We were aware that the original show, in our current social and political climate, could not be done exactly as written. Modern tastes and sensitivities have evolved. The show had some anachronistic portrayals of Native Hawaiians and African Americans. We wanted it to be an example of how to transform a show in this day and age. We kept the story intact as much as possible, and I believe we improved on it in a way that Abraham and his librettists would have approved of,” Frantzen says. He credits director Amy Hutchison with being at the forefront of the outreach effort to Chicago’s Hawaiian and Polynesian communities to ask for help in reformulating the dated portrayals in the original. “She did a brilliant job. We were able to not only straighten out these problematic sections of the script, but to incorporate Hawaiian language, dance and customs into the show.”

While the original operetta was designed to be pure escapism, historical politics were still woven throughout. Here, William Roberts plays John Buffy, assistant to the territory’s scheming American governor.

When the curtain opened on the sold-out shows in Chicago this summer, the infectious score propelled the operetta just as it had nearly nine decades ago. The beginning of the score features a Hawaiian steel guitar, just one part of a twenty-three-piece orchestra that also includes a trio of saxophones and a banjo. The set featured colorful larger-than-life flowers and tall painted cutouts of palm trees, evoking both the Jazz Age and Hawai‘i’s natural scenery.

Folks Operetta believes this is just the beginning for the revival of The Flower of Hawaii, and they may well be right. Aaron Mahi, who spent decades as the conductor of the Royal Hawaiian Band, has long been interested in staging Abraham’s operetta in the Islands; he was part of an attempt to do so in the early 1990s. “The idea was to use local artists and to redo the operetta in English and to translate the vocal selections into Hawaiian,” Mahi says. Now that the operetta has been so successful in the American heartland, it might not be too much longer before Abraham’s work is staged in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i—the language of Hawai‘i. HH