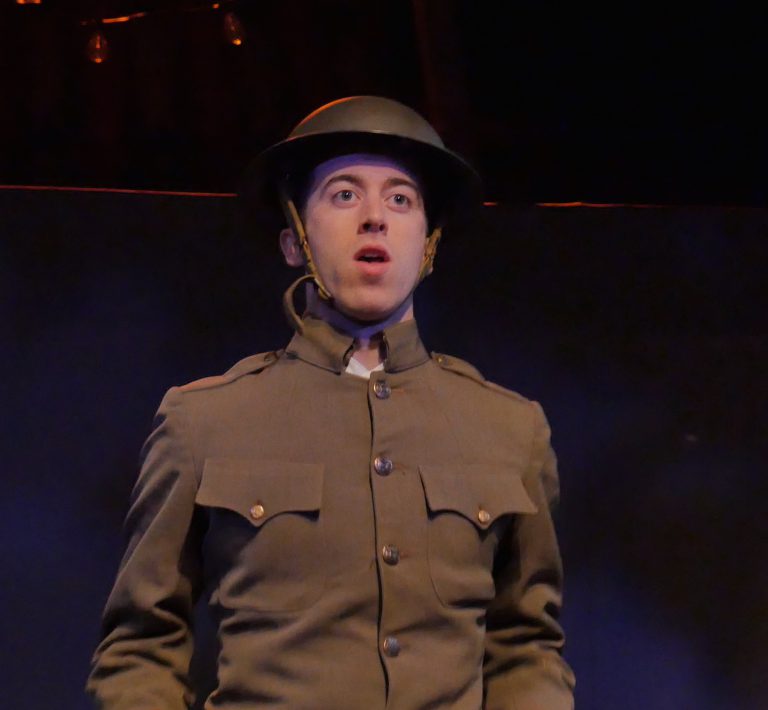

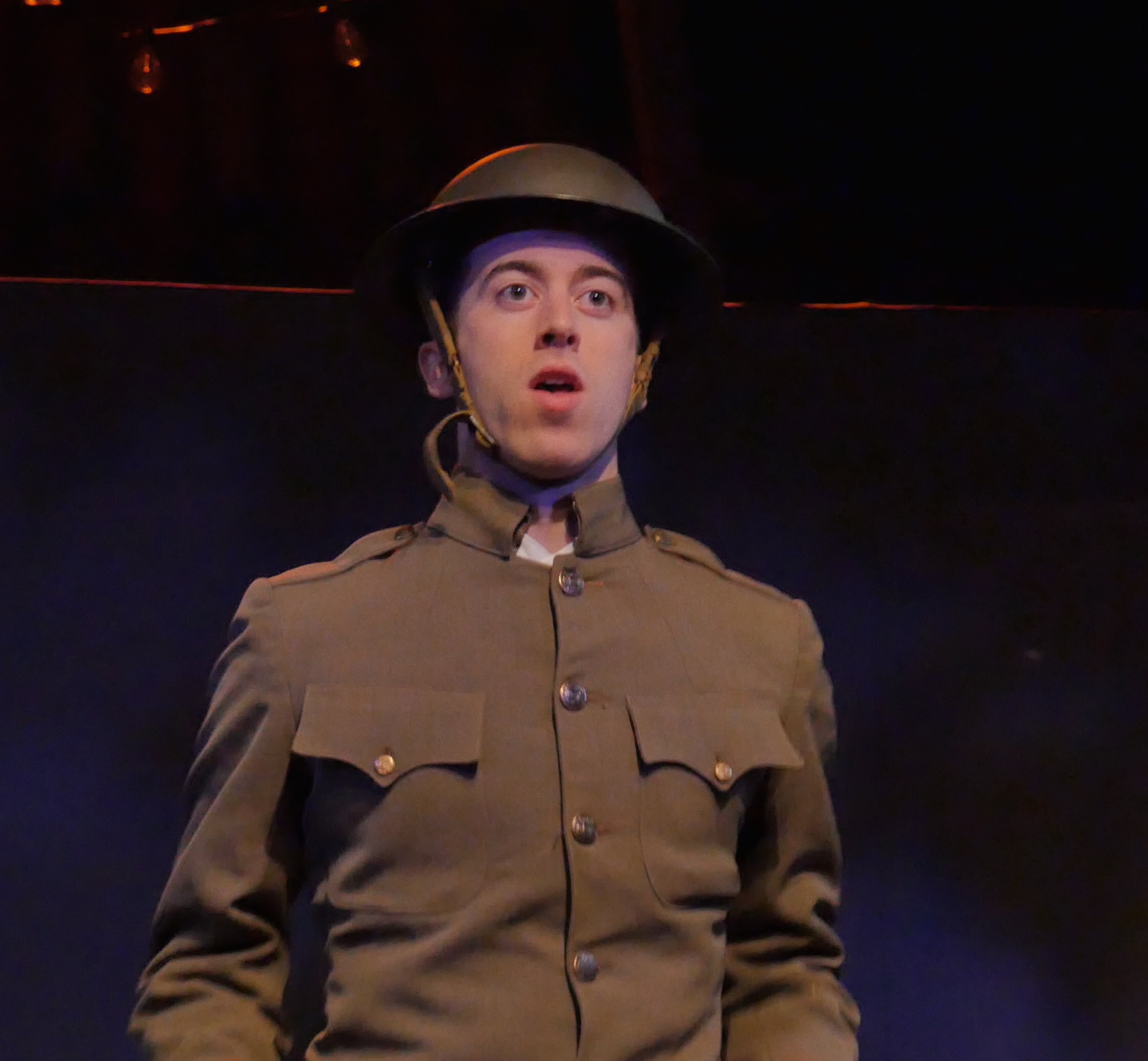

Chicago Premiere / Music by Kurt Weill

It is World War I. The United States of America, has pledged to remain neutral and is pulled into the fight in order to make the world safe for democracy “over there.” Lowly American tombstone cutter Johnny Johnson, has been persuaded to enlist in the U.S. army both by his sweetheart, Minny Belle Tompkins and by President Woodrow Wilson’s promise of “a war to end all wars.” But confronted by the horrors of the trenches in France, he is outraged at the absurdity of it all, and by dint of laughing-gas, he fools the Allied generals into calling a cease-fire. Johnny is arrested, shipped back to America, and locked up in a lunatic asylum for his “peace monomania.” Released some twenty years later, he makes a living selling handmade toys as the trumpets of war once more sound in the distance.

Program Notes by Dr. Timothy Carter

Johnny Johnson

The collaboration between playwright Paul Green (1894–1981) and composer Kurt Weill (1900–1950) must count as one of the more unusual in the annals of American musical theater. The German-Jewish Weill arrived in New York in September 1935 to work on Max Reinhardt’s biblical pageant, The Eternal Road (eventually staged in early 1937), although he knew he had left Nazi Germany for good. With a reputation as the enfant terrible of hard-hitting “political” theatre in the Weimar Republic—by way of working with Bertolt Brecht on Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera; 1928) and Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny; 1930)—Weill fell easily into the left-wing circles associated with the Group Theatre, which supported his efforts to break into the American theatrical scene.

Green, who taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was well known to the Group, which had done his The House of Connelly in its opening season in 1931. The advantage for Weill was that Green was a poet as well as a dramatist and so could write song lyrics as well as dialogue. The disadvantage was that the two of them came from quite different social and cultural worlds. Weill traveled down to to Chapel Hill in early May 1936, and he and Green then worked together at the Group Theatre’s summer retreat at the Pine Brook Club in Nichols, Conn., in June–August. As one of the Group Theatre’s directors, Cheryl Crawford, said, their aim was to write “an American anti-war comedy in almost review style.” Crawford also suggested various models, including George Büchner’s play Woyzeck (1837) and Jaroslav Hašek’s novel The Good Soldier Švejk (1921–22).

Green found the writing difficult: although he was in general interested in the uses of music in the theater, he struggled with how songs might work within dramatic action. Weill, too, had problems adjusting to the conventions of American musical theater, while the Group Theatre’s Stanislavskian methods made the presence of singing all the more troublesome. After a long rehearsal period and extended previews—during which the work was drastically cut—Johnny Johnson opened in New York at the 44th Street Theatre on 19 November 1936 and closed on 16 January 1937. But most reviewers, and especially the leftist ones, gave it some credit for its theatrical daring, and it was runner-up for a New York Drama Critics’ Award in 1937 (Maxwell Anderson’s High Tor won).

In December 1936, Green was approached by Hallie Flanagan, director of the Federal Theatre Project, for a possible FTP production of Johnny Johnson during its upcoming season of anti-war plays. The script he sent her restored almost all the cuts and alterations made by the Group, and it was used by the FTP in successful stagings in Boston and Los Angeles opening in May 1937 (another one by the FTP’s African American unit in Chicago was also planned but never came to fruition). However, Green continued to fuss with the play: he published a cut-down version of the text; he then revised it for staging in 1956 (after Weill’s death) and in 1971. But he was never entirely happy with the result.

The version of Johnny Johnson most faithful to Green and Weill’s original intentions is the one used by the FTP in Los Angeles un May 1937, which is the one adopted for the present production (with some minor cuts to the spoken dialogue). Although it rambles in places, it is hard-hitting, nay painful, in others. Not many would have dared to have a singing Statue of Liberty, or to give voice to three cannons looming over a World War I battlefield. Johnny’s story, and his final song, also have a beguiling sincerity that is all the more powerful for its time, with another world war on the horizon. It is a quite remarkable work.