By George Castle

Special to Chicago Jewish News July 2016

Even after the passage of seven or more decades, treasures by Jewish artists waylaid by the Holocaust are still being uncovered. Now the collaboration of Gerald Frantzen and Hersh Glagov are ensuring that some of these works do not stay literally unsung. Frantzen, co-founder of Chicago Folks Operetta, and chief translator/second violinist Glagov have crafted a combination revival/tribute to the Jewish composers and writers of popular operetta of the first three decades of the 20th century.

Music from the artists’ best works, and a narrative of their backstory and fate, will debut July 13 via Chicago Folks’ production of “Operetta in Exile: The Music Silenced by the Third Reich.” The new show will play at the 120-seat Stage 773 Theater, 1225 W. Belmont Ave. in Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood.

“We’re giving voice to those who were silenced,” said Frantzen. “No one knows their story. I wrote this show that tells their story and looks at their music. There’s been a resurgence in interest about Jewish classical composers that were forgotten and laid into obscurity by the war. But the guys who were really forgotten were the operetta people. We realized we had a responsibility because theirs is a story that has not been told.”

Part of the reason for that, said Glagov, is that “operetta is not on the map for most people in this country. Opera is well known; many cities have opera houses.”

Influenced by an injection of American jazz, operetta became a hugely popular entertainment in Europe in the first three-plus decades of the 20thcentury. Some of the popularity migrated across the ocean to the U.S. Operettas differ from all music and singing operas by having a combination of 75 percent music and 25 percent spoken word. They combine opera and musical form with a dash of humor blended in.

“From a Jewish perspective, you think about all the people who came over here and made important cultural contributions,” said Glagov. “For example, exiled librettist Alfred Grünwald’s son was Henry Grünwald, editor of Time Magazine. People are familiar with a lot of people who came over to Hollywood-writers, directors, composers. Those stories are better known than the operetta people. Jews have always had an outsized role in entertainment. The fate of the operetta people has been an unknown narrative facet of the Holocaust.”

Hungarian Jewish Operetta stars Rosy Barsóny and her husband Oskar Denés in Ball at the Savoy.

Glagov said “one of the things that this concert does so well is show some of the most important people in the world of operetta as the three-dimensional characters that they were. This makes their loss all the more horrible. I would just add that, to me as a Jew, these stories hit home on a personal level. It is impossible for me not think about what would have happened to my parents and grandparents, all of whom were alive at that time. Thankfully, they were all in this country. What if they had been caught in the wrong place at the wrong time?”

Operetta in Exile showcases the works of Fritz Löhner- Beda, whose status as librettist (story writer) for Hitler’s favorite composer Franz Lehár, the leading operetta composer of the day, did not shield him from a beating death at Auschwitz in 1942. Other artists whose classics contribute to the show are Fritz Grünbaum who died at Dachau in 1941; Paul Ábrahám, exiled to the U.S. but committed to a mental hospital in New York, Emmerich Kálmán, and cantor’s daughter/soprano Gitta Alpár, both of whom were exiled.

The Frantzen-Glagov collaboration is a labor of love in working nights, weekend and any other free moments. Frantzen founded Chicago Folks Operetta in 2006 with wife Alison Kelly, balancing his checkbook by singing in the Lyric Opera of Chicago chorus. Now his day job is selling men’s suits at Saks Fifth Avenue downtown Chicago. Meanwhile, Glagov- fluent in German and French- taught language at the Illinois Institute of Technology and the University of Chicago Lab School. Now he instructs in languages and violin at The Language and Music School of Oak Park.

The genesis for Operetta in Exile was Grünbaum’s writing for Peter and Paul in the Land of Nod(Peter und Paul im Schlaraffendland), a children’s operetta that debuted in 1906. “It was an innocuous children’s show all done in rhyming verse (German),” said Frantzen. “As we were translating it, we started looking further into the life of the writer. We’d been doing operettas for years. The tendency in operettas is to really focus on the composer and music, and not focus on the writer. I was shocked to find that this delightful little children’s show had in its background that Fritz Grünbaum was killed in a concentration camp. We started looking into his story and started to see a connecting string between other librettists and composers.”

Said Glagov: “We found some materials on-line, such as websites dedicated to music of that era. One site was devoted to musicians who died in the camps or otherwise in the Holocaust. I had a book called Operetta unter dem Hakenkreuz (Operetta under the Swastika). A lot of information from there made it into our concert.”

Frantzen’s research found that 90 percent of the operetta composers and librettists ) of the time were Jewish.

“It comes as no surprise, that the great librettists, people who wrote books and lyrics for these shows were Jewish,” said Glagov. “They had that sensibility, they grew up with it. The humor.”

Frantzen said some operetta composers and writers had a background in Yiddish theater. “It was a natural segue,” he said. Just recently there was a Yiddish operetta that was a huge hit in New York (The Golden Kale).”

Further triggering the project in 2013 was the company’s intention to revive the Hungarian Jewish composer Paul Ábrahám’s 1932 operetta Ball im Savoy (Ball at the Savoy). Frantzen found that Ábrahám survived the war, only to fall into living hell in New York city.

“Ábrahám was one of the most successful composers in Berlin just before the Nazis took over. He also wrote for film,” said Glagov. Frantzen added: “he was going to be the Andrew Lloyd Webber of his day. But his shows were shut down by the Brown Shirts.”

Ábrahám had two hit shows prior to 1932’s “Savoy”- Viktoria und Ihr Husar (Victoria and her Hussar-1930) and Die Blume von Hawaii (The Flower of Hawaii-1931). In these operetta, his musical style was a catch blend of traditional European operetta and American jazz. “Forced to flee Germany in 1933, he left several un-published songs at his Berlin villa,” said Glagov. “It is widely suspected that Ábrahám’s butler sold these songs to publishers under a different name, so that many songs that were hits in Germany during the Third Reich may have been written by this Jewish composer.”

Staying one step ahead of the Nazis, Ábrahám first went to Austria, then Hungary and Cuba, where he made a living as a pianist. He made his way to New York, but suffered a mental breakdown in 1946. He was institutionalized at Bellevue Hospital. In 1956, his admirers worked to bring him back to Germany, where he died in 1960.

Bohemian native Fritz Löhner-Beda’s story was even more tragic than Ábrahám’s. A natural comic, Löhner-Beda’s humor was published in his teen-age years. He was librettist for both Ábrahám and Lehár. “Löhner-Beda was proud of his Jewish heritage and openly criticized the Nazis,” Glagov said. “He was arrested in 1938 and sent to Dachau. Soon after that he was transferred to Buchenwald. There, along with fellow inmate Hermann Leopoldi, a well-known songwriter of the time, he wrote the Buchenwald Song, which was soon being sung by many of the prisoners there. The song expressed the yearning for freedom and the need to remember what happened there.” Of all the artists, Löhner-Beda touched Glagov the most.

“Löhner-Beda never pulled any punches about what he thought of the Nazis. When he was young in Vienna, there was a tendency for Jews to assimilate. He made fun of that. He said you should be proud of who you are. His integrity never faltered. He paid the highest price for it.”

Löhner-Beda was transferred to Auschwitz in 1942, dying as a result of a by German guards.

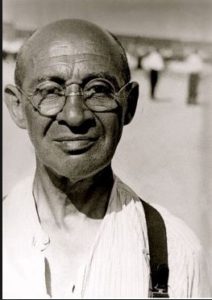

One of the last photos of Fritz Grünbaum at Dachau.

Grünbaum also died in Dachau. The Moravian native had been a near-Renaissance man, dividing his time between Berlin and Vienna as a librettist, cabaret performer, pop song writer and actor both on stage and in films. He went into hiding when the Germans took control of Austrian in 1938. Betrayed, he was captured and sent to Dachau.

“He put on shows to entertain his fellow prisoners,” said Glagov. “He died on Jan. 14, 1941, not long after a New Year’s Eve performance.”

The son of art dealers Grünbaum amassed an impressive collection of art. But his holdings were stolen by the Nazis. (The Grünbaum Collection is still being fought over in courts today.)

A bizarre storyline enveloped Hungarian composer Emmerich Kálmán, who staged his first successful operetta in 1908. He was regarded as one of the genre’s most important composers over the next three decades. His music was so popular in Germany he was offered the status of “honorary Aryan” by the Nazis. Refusing, he fled to the U.S. with his family. Returning to Europe after the war, Kálmán learned his sister had been killed in the Holocaust.

Emmerich Kálmán died in 1953 at the age of 71. But Chicago Folks Operetta enabled his works to live on, performing two of his operettas, Arizona Ladyand The Circus Princess. His daughter, Yvonne Kálmán, attended both shows.

Meanwhile top operetta soprano Gitta Alpár, another Hungarian, was connected with Ábrahám by performing in Ball at the Savoy. Fleeing to Austria in 1933, Alpár appeared in a film version of “Ball.” A stop in England preceded her emigration to Los Angeles. She never again reached her star status achieved in Europe. She died in 1991.

Other artists honored in “Exile” are Alfred Grünwald, Jean Gilbert, Leo Ascher, Robert Stolz, Leon Jessel and Julius Brammer. “The excerpts used in the concert are all relatively short, about five minutes each,” said Glagov. “We talk about a composer or librettist and then perform an aria or duet that he wrote. There’s at least one musical number to represent each composer or librettist we discuss.”

“Some of the musical numbers are in English and some are in German. The ones in English are drawn from the shows we’ve translated; the ones in German are from other shows that we haven’t translated yet. If the song is in German, we provide an English translation of the text in the program.”

Writer Frantzen and translator/editor Glagov had their challenges grafting English onto a German design. “It’s English words written for a German-language production,“ said Frantzen. “We have to make it fit, make it “singable.” The difficulty is to get the right emphasis, and what is comfortable to sing.”

Added Glagov: “If it’s a funny song, you’ve got to make it funny in English. You understand why it takes time to take German libretto and convert it to English. It takes several months.”

Frantzen, who is Catholic, credits Glagov with giving the right feeling to the songs. “Hersh brings to the translations that incredible Jewish with and humor, having grown up in that culture. Personally, I’ve always thought the best humor is Jewish humor.” Beyond the artists featured in the productions, other Jewish operetta performers, such as singers, are not scripted into the show. Instead, they are remembered in a visual display that includes vintage photos and art, the latter considered “degenerate” by the Nazis.

“One coquettish image is that of Betty Fischer, literally the poster girl for “Exile.” Jerry looked at a lot of old pictures, and the one of Betty was so striking he chose it for the promotional poster,” Glagov said.

“A singer, she performed in many of these operettas. She was quite famous in her time. Betty was like a number of the artists who were Jewish and performed all over Europe. She emigrated from Germany in 1933, returned to Europe after the war and died in Vienna in 1969.”

“Exile” will be staged during the run of Chicago Folk’s production of The Cousin from Nowhere, running form July 2 to 18 at Stage 77w. Professional singer from the Lyric Opera of Chicago and Chicago Symphony Orchestra Choruses will be featured. The Cousin from Nowhere has the same roots as the Jewish artist’s operetta, becoming a sensation in 1921 Berlin.

The combination of two productions, Frantzen hopes, will spur growth for Chicago Folks. Frantzen’s first priority would be a 300-seat venue, more than doubling his capacity at Stage 773. “We’re doing very large productions on a small theater budget. We use a 21 -22-piece orchestra, sometimes 24 singers. The performers are drawn to the genre, the instrumentalists are drawn to it, because it’s something new, fresh and challenging. Any violinist can take a church job, a wedding gig somewhere, and make twice as much. But they do it because they love the genre.”

Still, Frantzen believes operetta is in a kind of cultural no-man’s land. “Operetta is the bastard stepchild of the classical music and musical theater world,” he said. “We’re not really in the musical theater camp, and we’re not in the opera camp. In the Chicago theater community, we don’t know where we are. We are certainly part of the Chicago cultural quilt. This genre has gotten consistently good reviews. It’s accessible and enjoyable.”

Which is why Glagov hopes the Jewish community will come out to see “Exile.” “Appreciation of operetta is one reason,” said Glagov. “But it’s also understanding how these people were central, day-to-day cultural figures in their countries. And how they were uprooted. Every one of these people was singled out because they were Jewish, and each had to make tough decisions on how to survive.”